|

CSO: The Resource for Security Executives

|

|

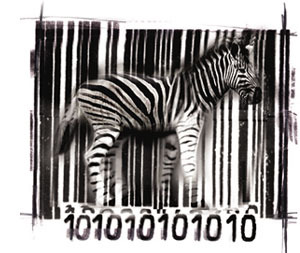

What Hides WithinNo longer just distinctive designs in paper, watermarks now are also patterns of bits embedded in digital contentBY SIMSON GARFINKELWATERMARKING BEGAN in Italy in the 13th century when papermakers used these marks to identify their handiwork. Eventually, specialized watermarks were commissioned. To impede forgery, for instance, governments created distinctive watermarks for official documents. To be effective, this required controlling the distribution of the resulting watermarked paper. The modern watermarking process is relatively simple: Papermakers spray wet pulp onto a moving belt and, before the mixture dries, press a design into the pulp using a device called a dandy roll. This dandy roll looks like an oversized printer's roller covered with a patterned wire mesh. The roll rearranges the paper fibers when it presses against the wet pulp, creating the watermark. Holding a finished sheet of paper up to the light reveals the pattern. Paper watermarks are less common today than they used to be. Most currencies have watermarks on them, as does expensive bond paper. (For example, some universities use special bond stationery bearing their official watermarks to send out acceptance letters.) However, such bond paper doesn't work well with laser printers or ink-jets; the result is that watermarks on paper will surely become a thing of the past. Desktop computers are quite good at mimicking the look and feel of paper watermarks. Some printer drivers allow you to print on every page a so-called background watermark—a faint gray image that does a pretty good job of simulating a traditional paper watermark. And Adobe's Acrobat Professional has an "Add Watermark" option under the program's "Document" menu that lets you add the watermark image of your choice to a PDF file. Printed watermarks offer nothing in the way of security or document authentication, of course—they're just there to satisfy aesthetic sensibilities. As in the pre-digital era, real security comes only with a mark that's hard to forge. "Digital watermarking" is an emerging concept, but don't let the name fool you. It's not used for authenticating documents. (That's the job of digital signatures.) Unlike a paper watermark, a digital watermark plays off that other sense of the word. It refers to the ability to unobtrusively include information in a file, and is commonly executed through a variety of cryptographic techniques, collectively known as "steganography." But instead of gently rearranging the paper fibers, digital watermarks gently rearrange bits scattered through a piece of digital content. One common use of watermarks is for embedding copyright information inside digital images, audio and video files. Watermarks are not text that might be put into a file's "comments" field; the watermark instead is put directly into the file's data, typically by making minor variations to pixel brightness. These variations are too subtle to be noticed by the human eye. The patterns are repeated many times, allowing the information contained in the watermark to be recovered even if the image is cropped. The best watermarks can even survive a limited amount of image manipulation, such as contrast adjustments or the use of sharpening filters. Digimarc has a sophisticated system for watermarking digital images called ImageBridge. The watermark can contain information such as the work's copyright year, a Digimarc ID, an image ID, a transaction ID and three specialized image attributes: "Restricted Use," "Do Not Copy" and "Adult Content." Graphic designers can easily embed, detect and read the watermarks by using Digimarc plug-ins bundled with image-editing applications such as Photoshop. The ImageBridge watermark makes it easy for law-abiding people to follow copyright rules. For example, you can download the watermarked photo of the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco from Digimarc's website. If you open it in Photoshop, select "Digimarc" from the Filter menu, and click on "Read Watermark," you'll see that the photo is watermarked with the ID 26017. Click on the "Web Lookup" button and Photoshop's Digimarc plug-in will take you to a page on the Workbook stock photography website. There you can discover that the image, "Sunlit sailboats below Golden Gate Bridge in fog, San Francisco Bay, California," was taken by Christian Michaels of FlashPoint Pictures and will cost $643 if you want to put its thumbnail on your homepage for a year. Of course, if you don't want to follow the rules, the watermark won't stop you. You could, for example, simply copy the image onto your website without asking for permission or writing a check to Workbook. But then, that would be stealing, wouldn't it? Watermarks can be used to help detect copyright violations. For example, Workbook could have a robot search the Web, looking for photos with embedded watermarks. Every time the program finds such an image, it could check with Workbook's database to see if the website has purchased an appropriate license for the image. But these robots can be defeated by breaking the watermark—for example, by modifying the image until the Photoshop plug-in reports that the watermark is no longer present. There are two ways to protect watermarks from being erased. The first is to encrypt the watermark so that only a special key could retrieve it. Watermarks that are encrypted are more resistant to attack because the attacker never knows for sure whether the watermark has been deleted. If you are especially devious you might even embed two watermarks in your image—one that's not encrypted, and a stronger, harder-to-erase watermark that is. This way, if you find an image that's had the first watermark deleted (but still has the second), you can argue in court that the infringement wasn't just willful, but that the infringer further attempted to hide his crime. Another way to protect watermarks is by designing a system that renders the watermarked file useless if the watermark is erased. For example, a company might create a special portable music player that plays only when presented with specially watermarked files. The business model might involve giving away the player and selling the files at a premium. Consumers would be free to erase the watermarks from the files, but the music wouldn't play on their players if they did. There are other possibilities for utilizing watermarks. A leading source of pirated DVDs and CDs is advance promotional copies that entertainment companies provide for industry insiders. Some record labels have started watermarking each insider's copy, making every pirated copy point back to the insider who was responsible for the infringement. This procedure may be shortsighted, however, because the insider may not have actually participated in the scheme. The crook might not turn out to be the music reviewer at The New York Times; she might instead be some college intern working in the label's mailroom who could have copied the disk and mailed it out with nobody the wiser. Watermarks can also be hidden in music that's played over the radio—another technique that could be used for tracking down piracy. But it could also be used to enable a new generation of "smart" radios that automatically display a song's title and artist. Once you start thinking about ways of hiding information with watermarks, a whole world of possibilities opens up—many of which can be rather unsettling. Computers could be gimmicked so that every page printed on your laser printer had a hidden watermark with your name, address, and date or time. Digital cameras could be set to automatically watermark their .jpegs with the camera's ID. Word processors could put hidden watermarks in document files. All of these techniques would make it easier, say, to track down who leaked confidential photos to the press or who put a copy of some military report on the Internet. All told, watermarking has come a

long way in the past 800 years. So has papermaking, of course.

Personally, I'm just glad that I no longer have to clean off my dandy

roll. PLEASE GIVE DETAILED INFORMATION ABOUT DIGITAL WATERMARKING PROCESS. GIVE DIAGRAMATIC EXPLAINATION. WHAT ARE ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES OF THIS TECHNOLOGY.

Sharath Mohandas

Swapna Raghuwanshi |

![]() Your comment will be displayed at the bottom of this page, at the discretion of CSOonline.

Your comment will be displayed at the bottom of this page, at the discretion of CSOonline.

Simson Garfinkel, CISSP, is a technology writer who is based in the Boston area. He can be reached at

Simson Garfinkel, CISSP, is a technology writer who is based in the Boston area. He can be reached at