| Identity Card Delusions | |||||||||||

The Net Effect April 2002

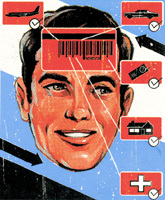

Mandatory national ID cards might cut down on underage drinking, but they wouldn't have stopped Richard Reid. | |||||||||||

Now the American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators, a kind of trade organization for the state motor vehicle registries, wants to make things official. This past January the association asked Congress for $100 million to link all of the state motor vehicle databases into a single national system, overhaul licensing procedures and phase in a new generation of high-tech cards. If this proposal goes through, driver’s licenses issued in two years will almost certainly be high-tech, biometric-endowed cards for the absolute identification of the cardholder. And this is just the beginning. Less than two weeks after the motor vehicle announcement, the U.S. Department of Transportation announced that it was moving full speed ahead with plans to create a nationwide “trusted-traveler” card—another biometrics-based national identification card. But instead of granting permission to drive, the proposed trusted-traveler card will allow the holder to breeze through security checkpoints at airports without being detained by lengthy interviews and intrusive searches. It has long since been a cliché to say that September 11 changed everything, but one thing that has certainly changed since that fateful day is America’s receptivity to the idea of a national identity card. Eight months ago, such cards would have been unthinkable, the first step toward an Orwellian surveillance society. But priorities have shifted. Many of those who once steadfastly opposed the ID card now see it as an unfortunate but necessary measure to protect “homeland security.” America is being sold an empty promise. The proposals for new biometrics-based identity cards will certainly let the states buy shiny new computer systems and deploy ominous Big Brother-style networks, and the cards will speed the passage of frequent travelers through the airports, but they won’t significantly improve the security of Americans. Indeed, had these systems been in place on September 11, they would not have prevented al-Qaeda’s deadly hijackings. The push to turn the driver’s license into a national identity card is coming not from the federal government but from the states. Motor vehicle administrators and police alike want to stamp out the scourge of fake out-of-state driver’s licenses—what many college students call their “drinking cards.” But replacing today’s patchwork of different-looking driver’s licenses with a single nationwide standard that’s all but impossible to forge will also confer many advantages for law enforcement agencies, because bogus out-of-state driver’s licenses are used by crooks engaged in identity fraud, people who keep driving despite their suspended in-state driver’s licenses and other assorted hoodlums. The states are also eagerly looking at biometrics as a powerful tool for verifying identity, preventing fraud and enlisting the driver’s-license database to help solve other crimes. States that digitize driver’s-license photographs can use face recognition systems to find out if the same person has multiple identity cards issued in different names. (Last year the Mexican Federal Election Institute adopted this technology to help stamp out duplicate voter registrations.) Likewise, states that collect fingerprints when issuing driver’s licenses can store that data in their automatic identification systems and then match it against fingerprints found at crime scenes. Many U.S. murder cases from the 1970s and 1980s that had gone cold were solved when fingerprints were brought online in the early 1990s. But moving this biometric information out of the states’ databases and onto the back of the individual’s driver’s license—one likely result of the September 11 attacks—would be a mistake. Technically, it is simple enough to do. A two-dimensional bar code, for example, can easily hold digitized representations of a person’s photograph, fingerprint or handwritten signature. And two years ago, the motor vehicle registries’ organization adopted a nationwide standard for encoding such information. Putting the information on the back of the driver’s license allows any business to use your biometrics to verify your identity. It also makes it that much easier for businesses to scan the information and add it to their files. Ironically, users of these new driver’s licenses would be more, not less, susceptible to identity theft, because so much more of their personal information would be in circulation. Instead of bar codes, our next-generation identity cards might contain computer chips. A typical chip card, or “smart card,” can hold more than a page of typed information. Some smart cards have encryption keys and tiny cryptographic processors, allowing them to engage in secure e-commerce-style transactions. In theory, a chip could allow multilevel access to the personal information that the card contains: a tavern, for instance, would be allowed to read your age, but not your name or address. Airlines would presumably be given access to the whole shebang, allowing them to use fingerprints or retina scans to biometrically verify the identity of every passenger boarding their flights. But despite their high-tech appeal, smart cards have a checkered track record when it comes to protecting the information they store. In Europe, where smart cards are widespread, hacking them to get free telephone calls or free satellite television is a cottage industry. If some U.S. businesses have access to the “secure” area of smart cards, I find it hard to believe that the relevant know-how and codes won’t, over time, migrate to criminal elements. Already, there are many cases of crooked clerks giving credit cards a second swipe at department stores and making their own copies of their customers’ credit card numbers. If some crook steals your fingerprint, you’re going to be vulnerable to a lot more than simple credit card fraud. What’s worse, the harder one of these new identification cards is to forge, the more valuable a forgery will become. It only takes one corrupt official to create a steady stream of fake, unforgeable IDs for the bad guys. And don’t forget, the government will need its own supply of fake IDs for undercover cops, spies, informants and the like. But what’s most disturbing about these new identification systems and policies is that they won’t accomplish their stated purpose—they won’t make Americans more secure against terrorists. As our leaders have told us time and again, the current war requires fortification of our homeland security to defend against a foreign threat. But foreigners traveling inside the United States are not required to get U.S. driver’s licenses—not even if they want to rent a car. Hertz, Avis and National Car Rental, for instance, will happily rent to any driver who has a valid license from Egypt, Israel or Saudi Arabia. If our officials are worried about more al-Qaeda “sleeper cells,” then they will be looking for people who have no former record—people who might even stand up to an FBI background check. Recording the fingerprints of an Egyptian businessman on the back of a Florida driver’s license won’t tell us if that person has a vial of smallpox in his shaving kit. And if some Saudi student with 100,000 kilometers in his frequent-flyer account and information about crop dusting on his laptop computer asks for a “trusted-traveler” card, he’ll probably get one. Like the FBI, which tucked a laundry list of new powers into the USA Patriot Act of 2001, the American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators and the Department of Transportation are using the terrorist attacks as a convenient excuse for deploying a national identification system that would have been politically untenable this time last year. Remember, even if the September 11 terrorists had been carrying smart-card-enabled driver’s licenses with biometric authenticators, they still would have been allowed to board their flights. American Airlines knew Richard Reid’s identity—it just didn’t know that he had plastic explosives concealed in his shoes. Forcing every American to carry a new state-issued identification card may cut down on illicit drinking and make things easier for police at traffic stops, but it is simply not a rational way to deal with the specter of terrorism. Better identification systems won’t do much to stop people who have evil in their hearts but not in their history. Simson Garfinkel writes on information technology and its impact. He is the author of Database Nation (O'Reilly, 2000).

| |||||||||||

| Home | Current Issue | Archive | ||||